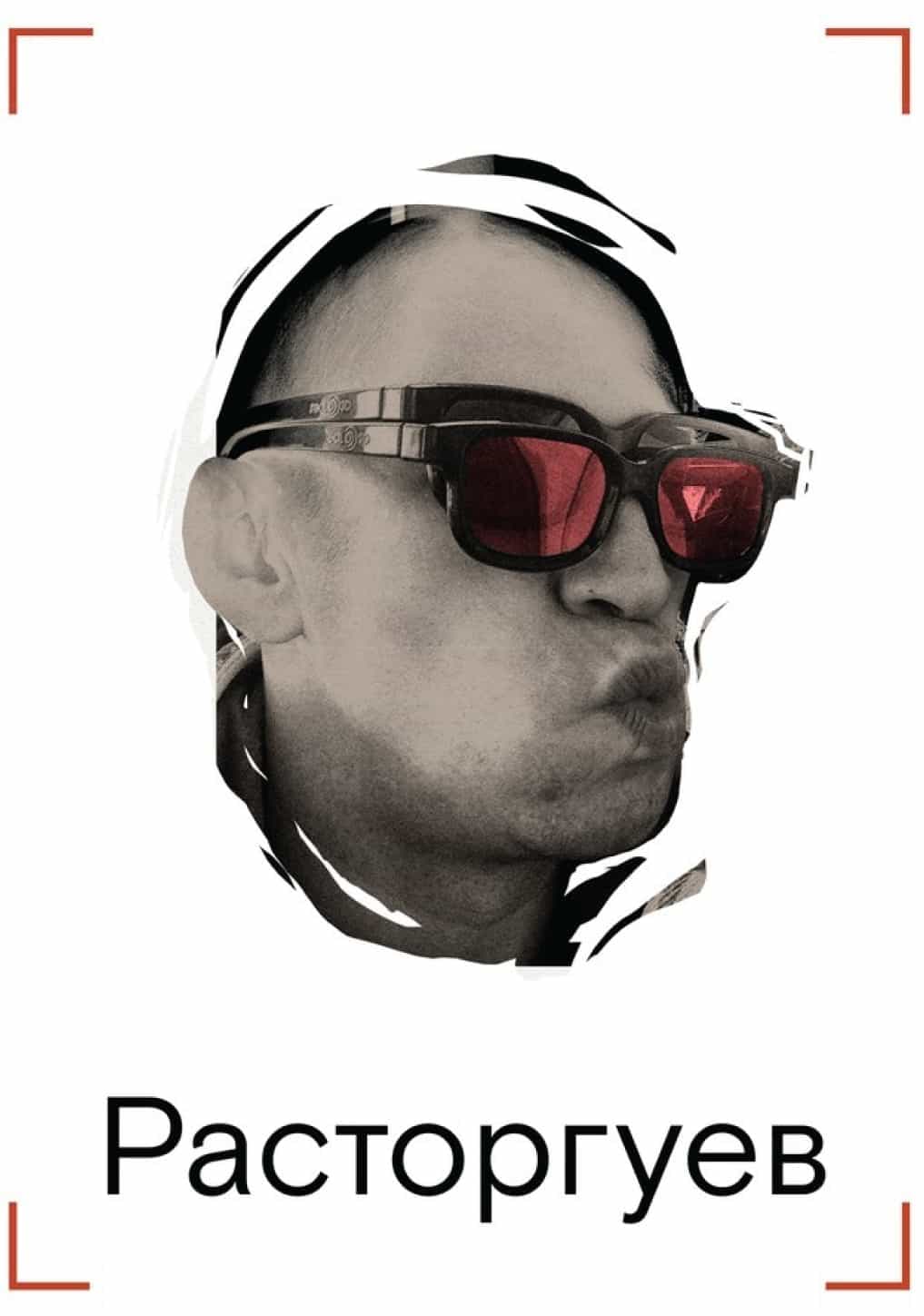

Alexander Rastorguev

Biography

Alexander Rastorguev was a documentary filmmaker.

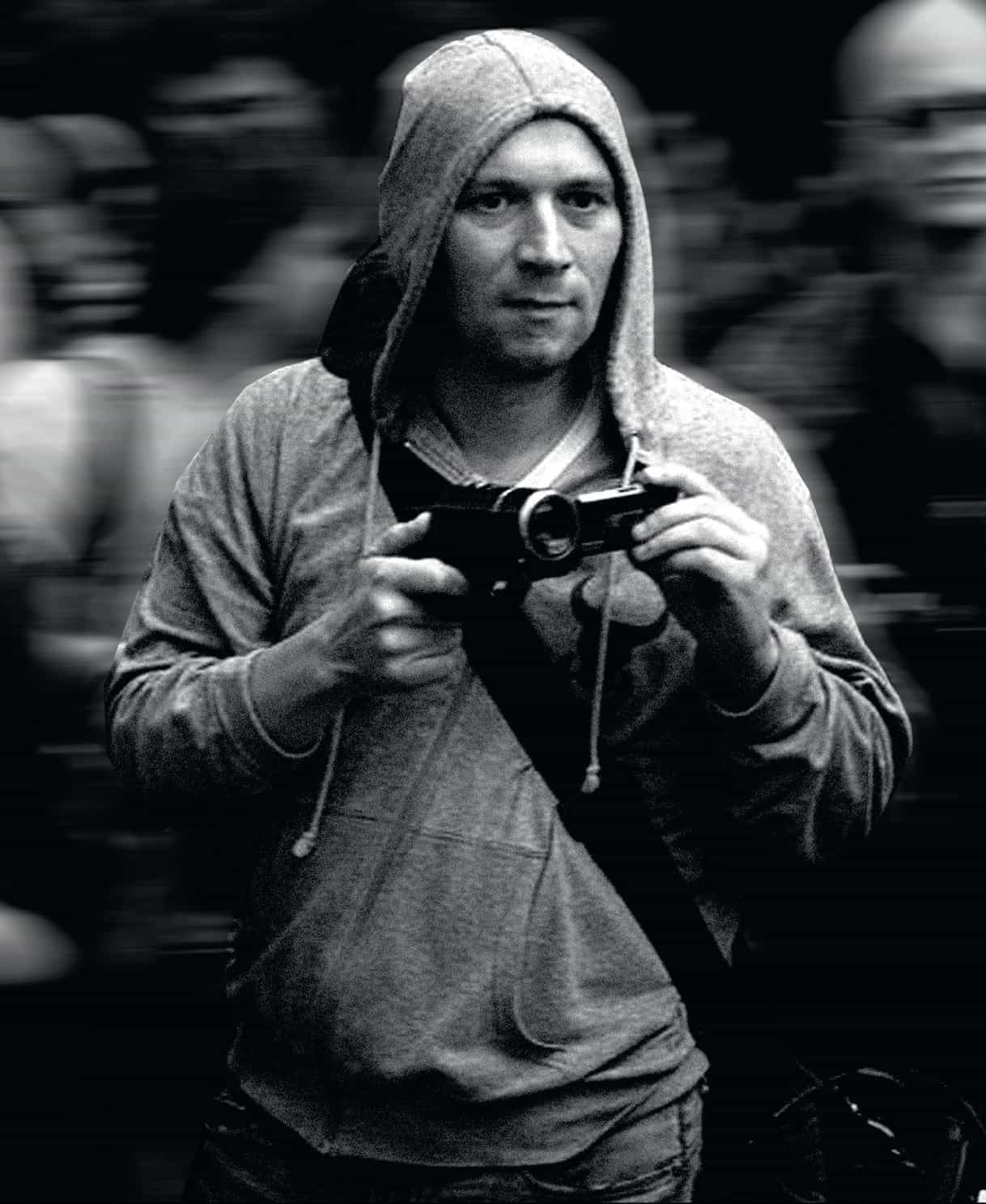

He was born on June 26, 1971, in Rostov-on-Don. He graduated from the Faculty of Philology at Rostov State University and from the State Academy of Theatrical Arts in St. Petersburg. Afterward, he returned to Rostov and began working at the Don-TR state television company. His Chisty Chetverg (Clean Thursday) documentary, about the war in Chechnya, caused a scandal: his co-author, Susanna Baranzhieva, was fired for “violating workplace discipline,” and Rastorguev resigned in solidarity. That early career episode seemed to define his creative method inseparable from his sense of self. He refused to obey, despised censorship, and resisted all constraints (“if the film requires showing the most horrifying scene, I’ll show it”). He did everything his own way.

All his films grew out of this conviction: freedom and nonconformism, absolute indifference to the boundaries between documentary, journalism, and activism. In 2009, he published a manifesto of new cinema on the Openspace website, lashing out at his colleagues for their inability to use freedom, to rebel, and to have opinions of their own.

There’s a naive attempt not to know what’s hidden. It’s as if a heap of facts were swept beyond the gates of mathematics: a bland life without the imaginary unit or irrational numbers in period. The degeneration of spiritual cement. Rusted mental rebar, dust. Fiberglass spun from documentary freaks. A few spices sprinkled on the sterile fast food of impotent, square little “ideo-films.”

He could not tolerate sterility and always went against convention, both in substance (to show everything, to hide nothing) and in form. If Zhar nezhnykh. Dikiy, dikiy plyazh (Tender’s Heat: Wild, Wild Beach )needed to last five hours, it could not be shortened. That was how he worked with his close friend and collaborator, cameraman and film director Pavel Kostomarov (I Love You, 2010; I Don’t Love You, 2012), and how he made the documentary project The Term (with Kostomarov and journalist Alexey Pivovarov, 2013). There’s no point in listing his full filmography – it’s available elsewhere – and even less in trying to force him into any conceptual box. After his death, his wife, Evgeniya Ostanina, made the film «rastorhuev» (the director’s handle on social media), which includes a telling fragment of footage:

— My profession is, in this sense, cynical.

— So you’re an egoist.

— I’m not. But I think it’s more cynical to sit and speak on behalf of another person—saying what I think—instead of letting them speak.

There’s a touch of irony here, of course. He knew better than anyone that a filmmaker can never be equal to a camera or a microphone, that the will of a documentarian can be stronger than that of a fiction director. This eternal contradiction, built into the craft, he simply ignored.

In the same film, he formulates what became his central creative wager: every human being, he says, must receive an ontological registration, a chance to be heard through the gaze of a thoughtful documentary director. He gave that chance to many people. He said much about himself through them.

Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic on July 30, 2018, together with two colleagues — the journalist Orkhan Djemal and the cameraman Kirill Radchenko. They had gone there to film a documentary about the Wagner Group. We still know little about the circumstances of their deaths.

Read everythingCollapse

All his films grew out of this conviction: freedom and nonconformism, absolute indifference to the boundaries between documentary, journalism, and activism. In 2009, he published a manifesto of new cinema on the Openspace website, lashing out at his colleagues for their inability to use freedom, to rebel, and to have opinions of their own.

There’s a naive attempt not to know what’s hidden. It’s as if a heap of facts were swept beyond the gates of mathematics: a bland life without the imaginary unit or irrational numbers in period. The degeneration of spiritual cement. Rusted mental rebar, dust. Fiberglass spun from documentary freaks. A few spices sprinkled on the sterile fast food of impotent, square little “ideo-films.”

He could not tolerate sterility and always went against convention, both in substance (to show everything, to hide nothing) and in form. If Zhar nezhnykh. Dikiy, dikiy plyazh (Tender’s Heat: Wild, Wild Beach )needed to last five hours, it could not be shortened. That was how he worked with his close friend and collaborator, cameraman and film director Pavel Kostomarov (I Love You, 2010; I Don’t Love You, 2012), and how he made the documentary project The Term (with Kostomarov and journalist Alexey Pivovarov, 2013). There’s no point in listing his full filmography – it’s available elsewhere – and even less in trying to force him into any conceptual box. After his death, his wife, Evgeniya Ostanina, made the film «rastorhuev» (the director’s handle on social media), which includes a telling fragment of footage:

— My profession is, in this sense, cynical.

— So you’re an egoist.

— I’m not. But I think it’s more cynical to sit and speak on behalf of another person—saying what I think—instead of letting them speak.

There’s a touch of irony here, of course. He knew better than anyone that a filmmaker can never be equal to a camera or a microphone, that the will of a documentarian can be stronger than that of a fiction director. This eternal contradiction, built into the craft, he simply ignored.

In the same film, he formulates what became his central creative wager: every human being, he says, must receive an ontological registration, a chance to be heard through the gaze of a thoughtful documentary director. He gave that chance to many people. He said much about himself through them.

Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic on July 30, 2018, together with two colleagues — the journalist Orkhan Djemal and the cameraman Kirill Radchenko. They had gone there to film a documentary about the Wagner Group. We still know little about the circumstances of their deaths.

The aims of art are the opposite

of the aims of power.

For art, like beauty,

has no purpose

other than humanity.

Films

This is not an archive, but a guide to the world of Alexander Rastorguev. We’ve gathered links to his films available from official sources.

Five works — Little Mothers, Gora, Wild. Wild Beach. Tender's Heat, I Love You, and I Don’t Love You — were shared with us by Evgenia Ostanina, the director’s widow, especially for this project.

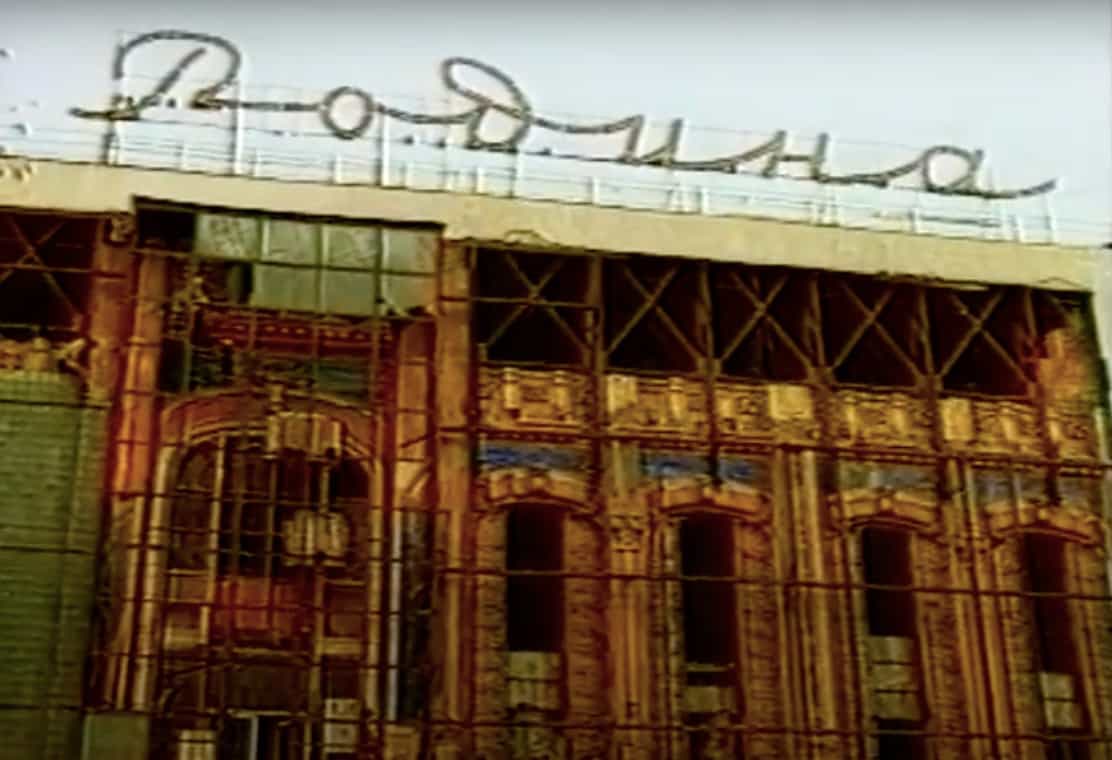

Rodina (Motherland)A film documenting the demolition of the Rodina cinema in Rostov-on-Don. As the building is torn down, passersby move through the frame — ordinary townspeople who, by chance, become part of the chronicle.25 minutes

Rodina (Motherland)A film documenting the demolition of the Rodina cinema in Rostov-on-Don. As the building is torn down, passersby move through the frame — ordinary townspeople who, by chance, become part of the chronicle.25 minutes Little MothersSixteen-year-old Yulia lives in a barracks; Vanya, with his parents in a five-story building. She’s expecting a baby, but his parents reject the match. Described by the director as “a monstrously real film about love”, Little Mothers is a dark fairy tale — a metaphor for Russian life.46 minutes

Little MothersSixteen-year-old Yulia lives in a barracks; Vanya, with his parents in a five-story building. She’s expecting a baby, but his parents reject the match. Described by the director as “a monstrously real film about love”, Little Mothers is a dark fairy tale — a metaphor for Russian life.46 minutes GoraA film about a woman living without a residence permit or insurance in a shack on the outskirts of Rostov-on-Don. Through her daily life, we see the lives of the inhabitants of a makeshift settlement on the site of a former landfill—with conversations, moonshine, and passions in a convent behind a brick fence.56 minutes

GoraA film about a woman living without a residence permit or insurance in a shack on the outskirts of Rostov-on-Don. Through her daily life, we see the lives of the inhabitants of a makeshift settlement on the site of a former landfill—with conversations, moonshine, and passions in a convent behind a brick fence.56 minutes Maundy ThursdayA war film without war. A field bath train near Grozny. In old train cars, soldiers wash, do laundry, and rest between battles. The camera captures the everyday life of soldiers: conversations, songs, vodka, memories of home—and rare moments of silence against the backdrop of ongoing war.46 minutes

Maundy ThursdayA war film without war. A field bath train near Grozny. In old train cars, soldiers wash, do laundry, and rest between battles. The camera captures the everyday life of soldiers: conversations, songs, vodka, memories of home—and rare moments of silence against the backdrop of ongoing war.46 minutes Tender's Heat. Wild Wild BeachA film about life on a wild beach on the Black Sea. Several intersecting stories of those who come here in the summer in search of relaxation without money and without plans. A human tragicomedy with conversations, clashes, and the vulnerability of people outside the official resort.2h 55m

Tender's Heat. Wild Wild BeachA film about life on a wild beach on the Black Sea. Several intersecting stories of those who come here in the summer in search of relaxation without money and without plans. A human tragicomedy with conversations, clashes, and the vulnerability of people outside the official resort.2h 55m Kids and MothersAt 39, Irina Gora found herself without a home — and unexpectedly pregnant by her friend’s son. Her child, Vanka, grew up quick-witted and kind. The camera follows him from birth to the age of eight: a whirl of scenes — the zoo, the Mormons, the city bathhouse. But one letter from Vanya to Putin turns their world upside down.1h 32m

Kids and MothersAt 39, Irina Gora found herself without a home — and unexpectedly pregnant by her friend’s son. Her child, Vanka, grew up quick-witted and kind. The camera follows him from birth to the age of eight: a whirl of scenes — the zoo, the Mormons, the city bathhouse. But one letter from Vanya to Putin turns their world upside down.1h 32m TheseA documentary film about the shooting of the film “How I Spent This Summer” in Chukotka. Three months of expedition to the polar station, the film crew lives and works in the extreme north — among bears, mosquitoes, and permafrost.59 minutes

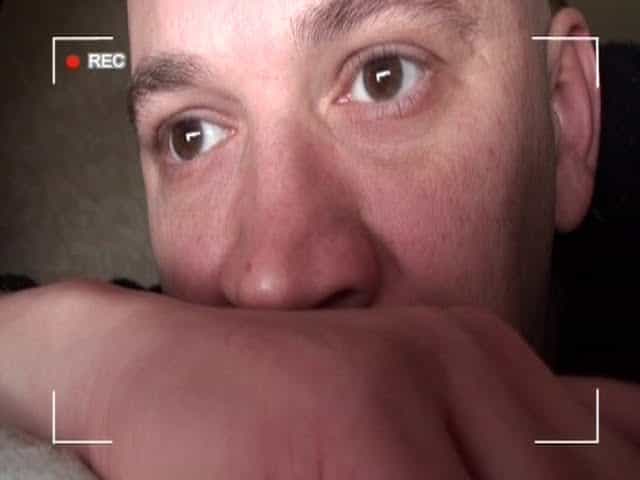

TheseA documentary film about the shooting of the film “How I Spent This Summer” in Chukotka. Three months of expedition to the polar station, the film crew lives and works in the extreme north — among bears, mosquitoes, and permafrost.59 minutes I Love YouA police officer’s camera accidentally falls into the hands of three teenagers from the suburbs. They film everything around them — the streets, their friends, themselves. Gradually, the game turns into a coming-of-age diary, where behind the jokes and mischief, something deeper appears: first love and the confusion of real feelings.1h 20m

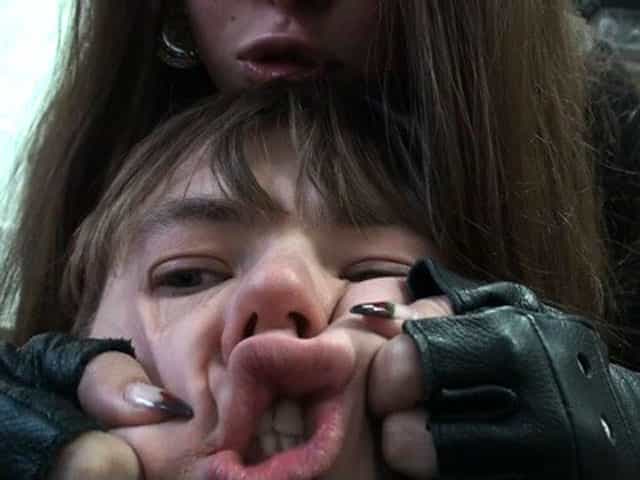

I Love YouA police officer’s camera accidentally falls into the hands of three teenagers from the suburbs. They film everything around them — the streets, their friends, themselves. Gradually, the game turns into a coming-of-age diary, where behind the jokes and mischief, something deeper appears: first love and the confusion of real feelings.1h 20m I Don't Love YouVika lives in the provinces and films almost everything on camera. She has Artem — sort of a boyfriend. But then Zhenya appears, and the love arithmetic begins: two suitors, one heart, and a tangle of doubts. While Vika hesitates, the camera records her life — full of flirting, confusion, and attempts to understand what love really means.1h 24m

I Don't Love YouVika lives in the provinces and films almost everything on camera. She has Artem — sort of a boyfriend. But then Zhenya appears, and the love arithmetic begins: two suitors, one heart, and a tangle of doubts. While Vika hesitates, the camera records her life — full of flirting, confusion, and attempts to understand what love really means.1h 24m TermFrom May 2012 to early 2014, a group of documentary filmmakers recorded daily short videos about Russian politics and protests. The feature-length film brings together the stories of key figures of the anti-Putin opposition — Alexei Navalny, Ksenia Sobchak, Ilya Yashin, Sergei Udaltsov, and Pussy Riot. The camera follows them at rallies, in courtrooms, behind the scenes, and in their everyday lives. Term is a story about the struggle for justice and the rise to popular fame — a story of love in times of conflict, and of how protest can become a way of life1h 22m

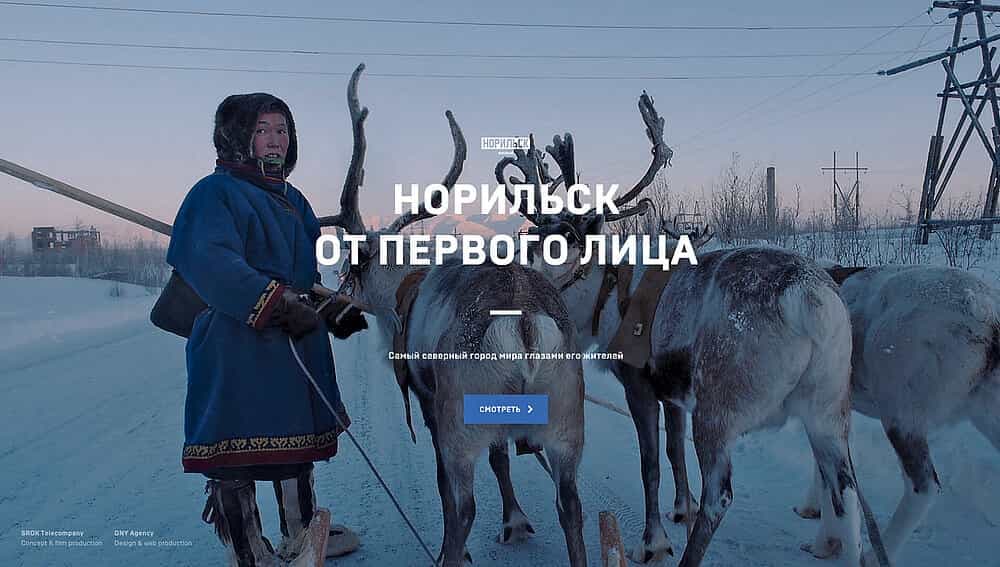

TermFrom May 2012 to early 2014, a group of documentary filmmakers recorded daily short videos about Russian politics and protests. The feature-length film brings together the stories of key figures of the anti-Putin opposition — Alexei Navalny, Ksenia Sobchak, Ilya Yashin, Sergei Udaltsov, and Pussy Riot. The camera follows them at rallies, in courtrooms, behind the scenes, and in their everyday lives. Term is a story about the struggle for justice and the rise to popular fame — a story of love in times of conflict, and of how protest can become a way of life1h 22m Norilsk in the first personWhen producer Alexei Pivovarov and director Alexander Rastorguev began working on a documentary marking the 80th anniversary of Norilsk Nickel, they moved away from the traditional format and turned to the genre of web documentary. The result was norilskfilm.com — an interactive website filled with short stories, archival materials, and virtual panoramas.42 minutes

Norilsk in the first personWhen producer Alexei Pivovarov and director Alexander Rastorguev began working on a documentary marking the 80th anniversary of Norilsk Nickel, they moved away from the traditional format and turned to the genre of web documentary. The result was norilskfilm.com — an interactive website filled with short stories, archival materials, and virtual panoramas.42 minutes This is me. Channel OneA television project filmed for Channel One. Women from different regions of Russia record their everyday lives on camera—without a script, without interference, without editing. Important: we are preserving this project as part of the history of independent documentary filmmaking. Despite the channel's reputation, the project was conceived as an honest and personal statement — and remains an important example of how Rastorguev worked.

This is me. Channel OneA television project filmed for Channel One. Women from different regions of Russia record their everyday lives on camera—without a script, without interference, without editing. Important: we are preserving this project as part of the history of independent documentary filmmaking. Despite the channel's reputation, the project was conceived as an honest and personal statement — and remains an important example of how Rastorguev worked. It's been three yearsAlexander Rastorguev’s final film tells the story of Alexandra Strizhenova, filmed over a span of three years. It portrays an ordinary woman — her daily life, her dreams of something better, her relationship with her son. Across its two parts, men and relationships change, but the struggles remain the same. Rastorguev completed two parts before his death in the Central African Republic; the film was left unfinished, with a sequel originally planned.1h 16m

It's been three yearsAlexander Rastorguev’s final film tells the story of Alexandra Strizhenova, filmed over a span of three years. It portrays an ordinary woman — her daily life, her dreams of something better, her relationship with her son. Across its two parts, men and relationships change, but the struggles remain the same. Rastorguev completed two parts before his death in the Central African Republic; the film was left unfinished, with a sequel originally planned.1h 16m Signs of Life: 20 short stories in collaboration with Radio LibertyDocumentary stories about domestic violence and the ways women cope with it; about the revolution in Armenia; about Alexei Navalny; about the 2017 Moscow protests; about a day in the life of an LGBTQ+ activist — and many others. None of them are about politics, but about people: their lives, their emotions, and a deep sense of humanism.

Signs of Life: 20 short stories in collaboration with Radio LibertyDocumentary stories about domestic violence and the ways women cope with it; about the revolution in Armenia; about Alexei Navalny; about the 2017 Moscow protests; about a day in the life of an LGBTQ+ activist — and many others. None of them are about politics, but about people: their lives, their emotions, and a deep sense of humanism.

In the Frame: Rastorguev

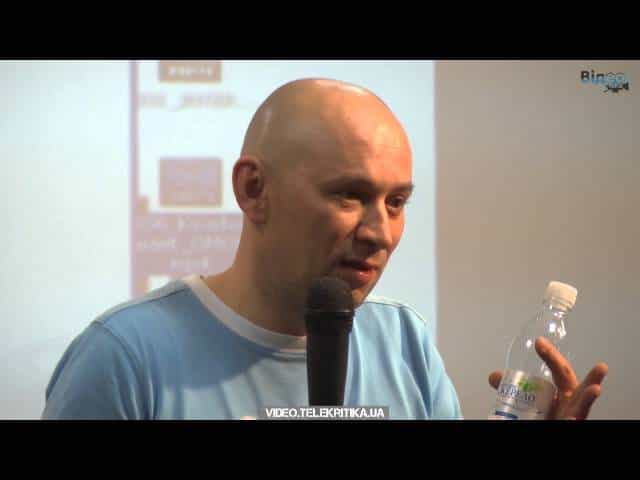

Film director Alexander Rastorguev. InterviewThe Russian director on why an author must “die” to survive, on his collaboration with Alexander Rodnyansky, and on the experimental film project Term.25 minutesYouTube

Film director Alexander Rastorguev. InterviewThe Russian director on why an author must “die” to survive, on his collaboration with Alexander Rodnyansky, and on the experimental film project Term.25 minutesYouTube Director Alexander Rastorguev, killed in the Central African Republic, on documentary filmmakingOn the evening of July 30, 2018, documentary filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic. Archive video showing the director discussing his craft.3 minutesYouTube

Director Alexander Rastorguev, killed in the Central African Republic, on documentary filmmakingOn the evening of July 30, 2018, documentary filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic. Archive video showing the director discussing his craft.3 minutesYouTube Alexander Rastorguev. Home Video / Observation DiaryFor 15 years, director Alexander Rastorguev has been filming what could be called documentary reality — capturing the raw lives of desperate provincials, without staging, censorship, or political correctness.9 minutesYouTube

Alexander Rastorguev. Home Video / Observation DiaryFor 15 years, director Alexander Rastorguev has been filming what could be called documentary reality — capturing the raw lives of desperate provincials, without staging, censorship, or political correctness.9 minutesYouTube Alexander Rastorguev on Moscow International Documentary Film Festival DOCER filmDocumentary filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev shared his impressions of watching the winning film at the 2015 Moscow International Documentary Film Festival DOCER, the Chinese film The Gleaners by director Ye Zuyi.5 minutesYouTube

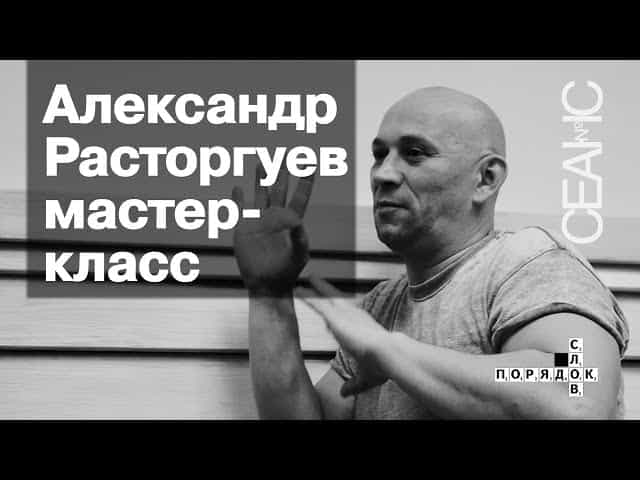

Alexander Rastorguev on Moscow International Documentary Film Festival DOCER filmDocumentary filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev shared his impressions of watching the winning film at the 2015 Moscow International Documentary Film Festival DOCER, the Chinese film The Gleaners by director Ye Zuyi.5 minutesYouTube Alexander Rastorguev. “I Don't Love You.” Master ClassSeptember 29, 2016. Alexander Rastorguev talks about the film “I Don't Love You.”54 minutesYouTube

Alexander Rastorguev. “I Don't Love You.” Master ClassSeptember 29, 2016. Alexander Rastorguev talks about the film “I Don't Love You.”54 minutesYouTube Master class by Alexander Rastorguev, part 116 minutesYouTube

Master class by Alexander Rastorguev, part 116 minutesYouTube Master class by Alexander Rastorguev, part 213 minutesYouTube

Master class by Alexander Rastorguev, part 213 minutesYouTube 30 videosYouTube playlist with interviews, master classes, and performances by RastorguevYouTube

30 videosYouTube playlist with interviews, master classes, and performances by RastorguevYouTube

In the Frame: about Rastorguev

Rastorguev at Artdocfest | Real CinemaOn the eve of the Rastorhuev film’s premiere, Vitaly Mansky, director Evgenia Ostanina, and producer Evgeny Gindilis remember Alexander Rastorguev — a filmmaker for whom there was no boundary between life and profession.18 minutes

Rastorguev at Artdocfest | Real CinemaOn the eve of the Rastorhuev film’s premiere, Vitaly Mansky, director Evgenia Ostanina, and producer Evgeny Gindilis remember Alexander Rastorguev — a filmmaker for whom there was no boundary between life and profession.18 minutes In memory of Alexander RastorguevA year ago, filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic. We still don't know how or by whom he was killed. But we do know how he lived and worked.6 minutes

In memory of Alexander RastorguevA year ago, filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev was killed in the Central African Republic. We still don't know how or by whom he was killed. But we do know how he lived and worked.6 minutes The Life and Death of Alexander Rastorguev [On the anniversary of the director's murder]...Rastorguev had a directing method that allowed him to take unrelated shots, a chaotic collection of seemingly unartistic material, and turn it not into a “documentary,” but first and foremost into a work of art.11 minutes

The Life and Death of Alexander Rastorguev [On the anniversary of the director's murder]...Rastorguev had a directing method that allowed him to take unrelated shots, a chaotic collection of seemingly unartistic material, and turn it not into a “documentary,” but first and foremost into a work of art.11 minutes Remembering Alexander RastorguevVitaly Mansky, Lyubov Arcus, Pavel Kostomarov, and Susanna Baranzhieva discuss the director.6 minutes

Remembering Alexander RastorguevVitaly Mansky, Lyubov Arcus, Pavel Kostomarov, and Susanna Baranzhieva discuss the director.6 minutes

Beyond the obvious, one must turn the camera toward oneself.

Place it in the hands of the very person whose story it tells.

In the text: Rastorguev

- My heroes are my executioners

Journalist Elena Vanina recounts the life and tragic death of director Alexander Rastorguev, whose documentaries blurred the line between author and subject, turning his interviewees into the “executioners” of their own stories and revealing the truth through personal encounters with reality.

- Alexander Rastorguev, co-author of the film “I Love You”: “And people watch TV and think, ‘Spiders are fighting in a jar.’”

The creator of the Natural Cinema manifesto explains why provocation and obscenity are necessary in film.

- Alexander Rastorguev. Interview, archive

In conversation with Lyubov Arkus, Alexander Rastorguev reflects on directing as both will and truth, explains why provocation in film can serve as a way of “extracting” a more honest reality, and shares his thoughts on fear, limits — including financial ones — and on intimacy and betrayal within the filmmaking process.

- Rastorguev. A Book Like Its Protagonist

Film critic and publicist Zoya Svetova discusses the creation of the documentary novel Rastorguev, in which the director appears “as if alive” through the texts of his loved ones, interviews, and personal manifestos, and explains how compiler Lyubov Arkus achieved the “impossible” — making the book resemble its protagonist.

- Alexander Rastorguev's page on Chapaev.media

- Alexander Rastorguev's page in Seance magazine

- “He dug in, bit into life, got under its skin.” Vitaly Mansky — in memory of director Alexander Rastorguev

- rastorhuev: I really like rain and all that... — Zara Abdullaeva on the film Rastorhuev

- Correspondence between Alexander Rastorguev and Lyubov Arkus

- Five major films by Alexander Rastorguev available to watch online — stories about vacationers, single mothers, soldiers in Chechnya, and the opposition.

- Different documentaries. Five years since the death of Alexander Rastorguev

- In memory of Alexander Rastorguev: films, footage, and words from the director who is no longer with us

- The life and death of director Alexander Rastorguev. On the anniversary of his murder

- About Rastorguev | Colta.ru

- Goodbye. A Guide to the Films of Alexander Rastorguev

- Honesty and purity: What director Alexander Rastorguev will be remembered for

- Friends and colleagues remember Orkhan Dzhemal, Alexander Rastorguev, and Kirill Radchenko, who were killed in Africa.

- Alexander Rastorguev: from Realism to Surrealism

- Manifesto of Tenderness: Ksenia Rozhdestvenskaya on the book Rastorguev and its protagonist